The past weekend in New York was characterized by loud, cacophonous protests against police brutality, and tense clashes between protesters and law enforcement. But while most protesters directed their vitriol at the system as a whole, a smaller group of protesters targeted four specific Manhattan lawmakers.

Last Saturday, the advocacy group Fight for NYCHA’s held their “March Against Racism and Austerity”, which spanned from Midtown down to Union Square. The march had the group speak out on a plethora of issues, most prominently police brutality and budget austerity measures that have left NYCHA and Medicaid with insufficient funding.

“We’re constantly told that there’s no money in the budget for NYCHA,” said activist Marni Halasa. “Yet there’s money for everything else; there’s money for the NYPD, there’s $8.7 billion for new jails. But there’s never any money for NYCHA.”

On the way, they stopped outside the apartments of Council Speaker Corey Johnson (D-Chelsea, Hell’s Kitchen); former Council Speaker Christine Quinn (D); State Senator Brad Hoylman (D-Chelsea, Midtown); and Assemblymember Deborah Glick (D-East Village, West Village). As Fight for NYCHA representative Lewis Flores explained, there were two primary reasons why his group targeted these four lawmakers specifically.

The first was that he found the lawmakers guilty of what he called “pink-washing”. Johnson, Quinn, Hoylman and Glick are all openly gay, and thus have experienced systematic discrimination and oppression. But even though they know from experience that the system privileges certain groups over others, Flores believes that they haven’t done enough to uplift other marginalized groups – most notably people of color.

“These four electeds came to power as a result of a need that existed at the time, for LGBT representation in government,” said Flores. “I’m a gay activist myself, and I don’t besmirch them for that. My problem is that these politicians claim they experience discrimination and oppression, but they haven’t done anything of material value to help end racism.”

In particular, they accused the lawmakers of failing to hold the NYPD accountable for police brutality, which disproportionately affects racial minorities.

Secondly, Flores and his peers held the four lawmakers responsible for the closure of St. Vincent’s Hospital. Founded in Greenwich Village in 1849, the nonprofit Catholic hospital was a vital source of healthcare for low-income New Yorkers of color for over 150 years. On Apr. 30, 2010, the hospital had to close due to mounting debt and other financial woes, despite the best efforts of the community to keep it open.

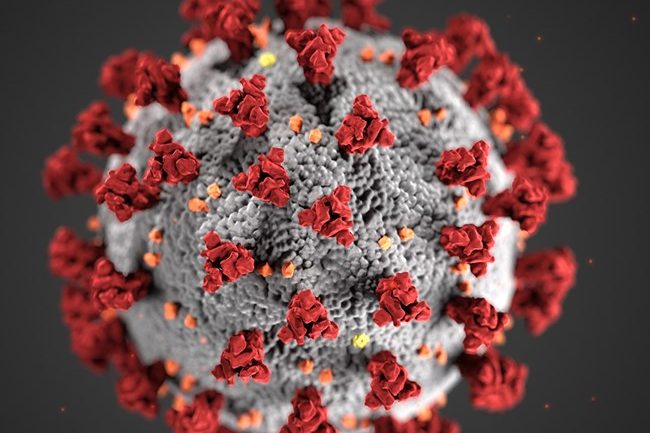

Fight for NYCHA has speculated that the neighborhood would have been far more prepared to handle the COVID-19 pandemic if the hospital were still open.

“St. Vincent’s was a charity hospital; its mission was to serve the poor,” said Flores. “The closure of the hospital has put all of these communities at risk. At least 1,200 people [in NYCHA] have died from the coronavirus.”

Flores claimed that Johnson, Quinn, Hoylman and Glick were either responsible for or complacent in the hospital’s closure. At the time, Quinn was the Council Speaker, Johnson and Hoylman were serving on Manhattan Community Boards, and Glick held the same Assembly seat that she holds to this day.

“In this community, there are four politicians who claim they know discrimination and oppression,” said Flores. “But they’ve turned their back on people of color. To this day, they’ve done nothing to replace this hospital.”

When asked, Brad Hoylman denied any such responsibility for the closure. Although he was serving on Community Board 2 at the time, he said that the position gave him no such power to keep the hospital open. As he explained, the decision not to bail out the hospital lied with the New York Public Health and Health Planning Council (PHHPC), which neither he nor Johnson nor Quinn nor Glick have ever been a part of.

Furthermore, as a State Senator he has sponsored legislation to expand the number of consumer representatives serving on the PHHPC. This, he said, would prevent more of these closures from happening in the future.

“Since taking office, I’ve fought for more hospital dollars and more consumer representation in health planning,” said Hoylman. “The public is seeking more input into health planning, which I wholeheartedly support.”